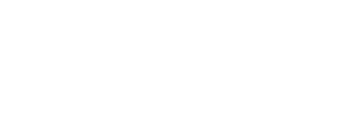

MYSELF MONA AHMED

20.3 x 17.8 x 1.7 cm

Hardcover

Scalo Publishers

ISBN 10: 3908247462

ISBN 13: 978-3908247463

Publication date: 2001

On the day of my assignment, I walked around a Delhi neighborhood with extremely narrow lanes, asking for Akbar Milkman’s Lane, looking for the house of the legendary eunuchs Sona and Chaman. I had already heard of this beautiful duo of eunuchs, famous for their performances at weddings. During the partition of India and Pakistan, Sona went to Pakistan, and Chaman stayed on in India. 45 years later, people in Turkman Gate, the neighborhood where they lived, still spoke of them with awe. My appointment was with Chaman’s student, Mona Ahmed. Mona is a female name and Ahmed is a male name. To me, she is just Mona, but to her family she is Ahmed.

The lanes seemed to get even narrower as I got closer to Mona Ahmed’s house. Terrified, I rang the musical bell and was greeted by a very handsome eunuch, fully made-up and wearing lots of jewelry. “Welcome to my house,” she said. I was amazed at the warmth with which I was greeted not just by Ahmed, but also by all the other eunuchs living in the household that Chaman headed. I was charmed by the very same eunuchs who had once terrified me on the streets of Delhi by threatening to lift their skirts, if I did not pay them money for a blessing. Girls from good families were not supposed to look up when they lifted their skirts. In Hindi they are called hijras, almost an abuse, and giggling schoolgirls would call them ‘it.’

To my surprise, Mona agreed to be photographed, and we spent the entire day shooting. However, she changed her mind upon hearing that the photographs were for the London Times, and not the New York Times, as she had relatives in the UK who did not know about her being a eunuch. She asked me to return the film. I did not have any choice and returned the film to her. The eunuch story ran in the Times with an illustration, instead of a photograph, and I told my dear colleague Chris Thomas that the film had gone bad in the processing. I was too ashamed to say that it had been forcibly taken away from me, though I am sure he would have understood. Mona embraced me when I returned the film, which she threw into the garbage. I am not sure I was quite aware of the bond that had been created, and how much of a part of my life Mona would become.

I would like to think that I understood that she was afraid of offending her relatives who had known her as male. Frankly though, I was just so scared of being in a house full of eunuchs that I returned the film because I was afraid that they might beat me up. Eunuchs seem frighteningly large and loud when you encounter them on the street, or when they refuse to leave your house without being paid for their blessing, clapping the loudest claps you will ever hear. I was in no position to incur their wrath, particularly not in their own territory. When eunuchs come to your house, and you start to fight with them, not even the police will interfere.

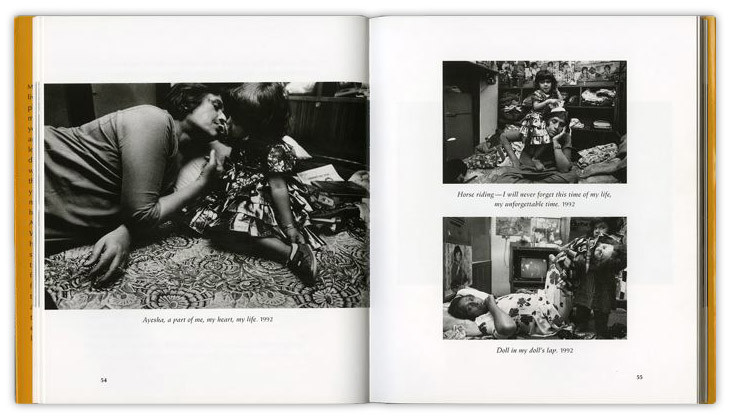

In India, every city is divided into neighborhoods, each of them assigned to a group of eunuchs who will give blessings in the area and claim money for them. No other eunuch can ask for money in the area. The eunuchs have a script to mark the houses they have been to. People believe that as they are neither male nor female, their blessings and curses may have magical powers. Thus most people are unwilling to run the risk of their curse at the start of a marriage or when moving in a new house. In the olden days, Mona told me, the eunuchs were often invited by the families to come and give their blessings at various ceremonies. Almost every family had their ‘family eunuch.’ Now, however, as city dwellers have fewer children and have started to employ security guards, times are getting harder for eunuchs and they are branching out of their traditional roles.

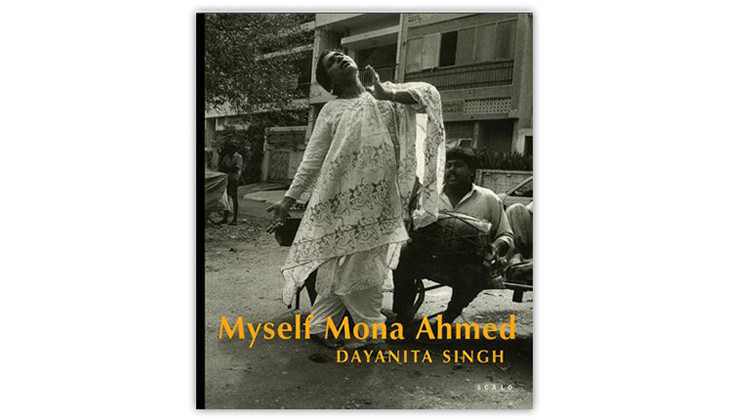

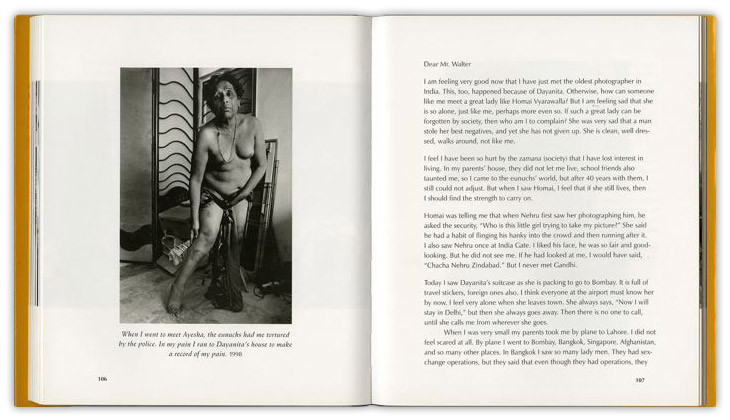

Some time before I got to know her, Mona adopted a baby girl named Ayesha. Her birthday parties lasted 3 nights, and even eunuchs from Pakistan would attend the festivities. Somehow, an unusual trust between Mona and me had developed by then, and I was the chief photographer at these celebrations, a rare honor in the self-closed eunuch society. Whenever I was passing through Delhi, I would wander towards Turkman Gate and spend hours lying around in Mona’s room.

In the house, we were like two old school girlfriends, Mona advising me on my relationships and suggesting projects I could work on in my photography. When we were on the street, however, she became my protector. If anyone in her neighborhood dared to question what I was doing there, or why I took photographs, she gave them a mouthful. Although usually a look was all it took. I always knew that if I were stranded somewhere in Delhi, Mona would come and get me home safely.

This was in the early years of our friendship. As the years went by, and we both got older, the equation shifted. More and more, I felt that I had to take care of Mona, especially after Ayesha was taken away from her and she moved to the graveyard. More than anything else losing Ayesha broke her heart. Sometimes, I was irritated by my new role of mothering Mona and I would tell her. Once again, she surprised me by her understanding of the situation. Once, I complained that I felt somehow guilty when she asked me why I had not yet returned to Delhi, Something no one ever asked me, not even my mother since the age of 18. Mona simply replied, “Well, that is because you have become English in your love. You have forgotten Hindustani love: if I ask you why you did not return when you said you would, it is my way of expressing love. But if it annoys you, I will not ask.”

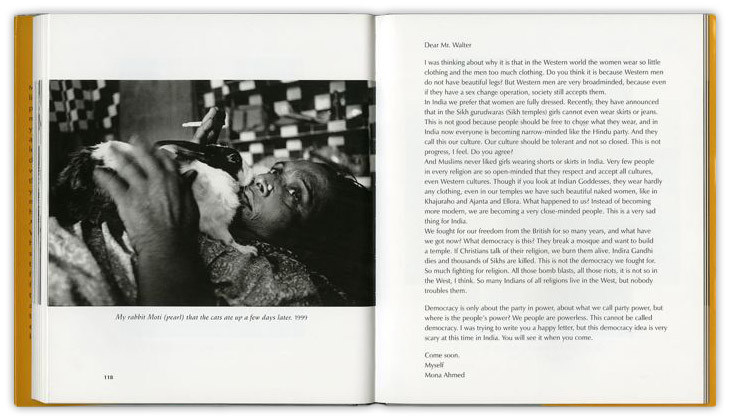

Mona never came to my house empty-handed. She would always bring at least a bag full of fruit. When I went with her to visit her eunuch friends, they would give me money, as a present for gracing their house with my presence for the first time. Even after Mona’s problems with the other eunuchs started, Chaman Guru came to bless my new apartment, throwing rice in every corner and blowing some words into the air. When Mona thought that I was going through a bad time, she would take red chilies and make circles around me to send away any evil spirit. Even now in the graveyard, she is constantly counseling women who have been left by their husbands, or who have sexual problems, or who are abused by their husbands. She told me a hilarious story about the woman whose husband had died and who wanted to be buried next to him. By the time the woman got the money to buy the plot next to her beloved husband’s grave, another woman had already bought the place. Mona laughed at her and said, “See, even in death he keeps another woman between the two of you.”

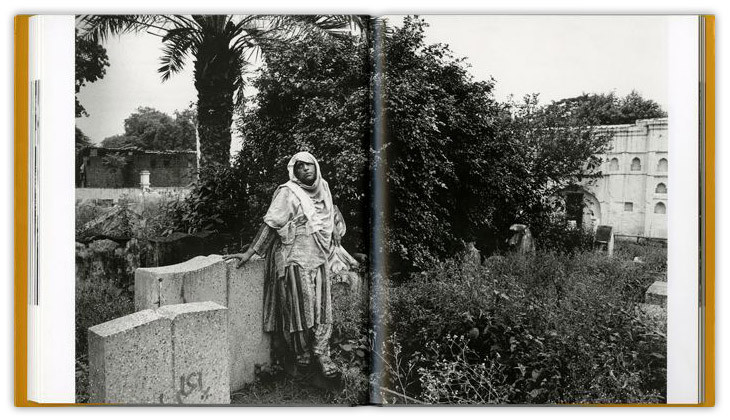

It is true that Mona has lost all of her glory, as she says. She used to be the self-appointed empress of Turkman Gate, but once she left the eunuchs, people turned their eyes away from her. In the graveyard where she now lives in a house built on her ancestor’s graves, she is building a palace. The swimming pool has already been dug out, but I have managed to convince her that even a waterfall and a swimming pool will not make people want to rent the marriage hall she wanted to build. She also considered starting a pickle factory in the empty pool, employing Muslim women who had nowhere to go. She would call them ‘Ahmed Pickles’ and wondered whether Scalo could sell them in Switzerland. Forever full of new ideas, Mona would now like to convert the palace she initially built for Ayesha into an orphanage for Muslim girls, so she would be the mother of a hundred children, not just one.

Through Ayesha, through all the animals, through the crazy ladies in the graveyard, Mona has repeatedly tried to recreate a family for herself. Once again, she has an army of animals, and all the little children living around the graveyard are gathered around her TV set. Yet, finally her inner loneliness is eating her up, the feeling that she belongs nowhere, an outcast among the outcastes. When I tell her that she is such a unique person, that she would be a misfit in any society because of her very unique point of view, she is not convinced. She claims that if she were wealthy like me, she would be accepted in society.

Two years ago, I wrote her a fax about this book two years ago, unsure about how she would react. I wrote, “A publisher would like to make a book with you, about your unique self.” She wrote back to me, through my mother, and said that she was delighted. But she also wrote, “The whole world calls me a eunuch. You call me unique, which is true. I am very confused.”

When I once asked her if she would like to go to Singapore for a sex change operation, she told me, “You really do not understand. I am the third sex, not a man trying to be a woman. It is your society’s problem that you only recognize two sexes.” Although later she told me that she was probably the first person in India on whom a doctor had tried to perform a surgical sex change (which is still illegal in India). She took a fellow eunuch whose nose had been cut off to a plastic surgeon who in turn offered to test a sex-change operation on Mona. Her sex-change operation had to be performed in three phases, but she gave up after the first step as it was too painful. She knew from the Lady Boys of Bangkok that an artificial vagina had none of the sensations a female vagina was capable of.

Mona is one of the most precious gifts photography has given me. In this class-ridden society of ours, there would be no meeting point for Mona and me, were it not for photography. Photography led me to her, but it was not photography that sustained our relationship for more than 12 years. My colleague Tim McGirk wrote a story on her in the Independent magazine in the early 90s. She decided that she would have nothing to do with journalists, even though she liked Tim. She feared that they were only interested in the details of her castration, how the blood felt as it ran down her thighs, but not in her heart or mind. Over the years, I photographed her off and on, with no intention of ever publishing the photographs. It was only many years later, after Mona was thrown out of the eunuch’s community and she became an outcast among the outcastes, that she told me that she wanted to tell her own story. She was now living in a double exile, and started to question her identity in a way that was completely new to me. She wanted to tell the story of being neither here nor there, neither male nor female, and finally, neither a eunuch nor someone like me. She would always ask me, ”Tell me: what am I?” I first assumed that a writer would have to tell her story, but after she dictated me some e-mails, I realized that I probably underestimated her and that she could tell her own story, weaving together fact and fiction.

Mona is extremely critical of her images and immediately rejects those that play, however inadvertently, on her oddness. She is also very upset that I never photographed her with my Hasselblad. She said, ” You photograph rich peoples with rich man’s camera. Why do you photograph me only with a small camera?” She even went on to say that if my wealthier friends could be photographed as though they were royalty, why couldn’t she. She referred to my series of family portraits in which my subjects decided where they wanted to sit and what they wanted to wear. Yet Mona must have known that her photographs with me were increasingly a fantasy. She would dictate, and I could never argue with her. For the first photo in the book, with her sitting on the rocks, her head covered, she took me to the place, sat down, covered her head, and said, “Now, take my Pakeeza (heroine of an iconic Hindi film of love and longing) photo.” I tried to argue, saying it was too filmy, but she insisted, as with the one where she is standing alone among the flowers. But I was never able to photograph her seductive manners, her coy side that would emerge in the company of my male friends.

As I now am thinking about which city and country I would like to live in, what kind of home and family I would like to have, my two main concerns are my own photography, which is profoundly rooted in India, and my dearest friend Mona. More than my mother, more than my friends and my sisters, it is Mona I worry about. Yet, unique as she is, she will probably react in a way that will take me by surprise and make me realize once more that I underestimated her generous mind.

– Dayanita Singh, Myself Mona Ahmed, 2001

It’s her story – The Hindu, 3 February 2002

From Eunuch To ‘Unique’: This Photo Story On Mona Ahmed Is Incredibly Poignant – Neville Bhandara, Homegrown.in, 2 September 2015